|

|

Reel Classics > Stars

> Actresses >

Alida Valli

Article | Downloads | Image Credits

|

Often the difference between ordinary beauties and beauties who find success

in motion pictures is not the degree of photogeneity in the face but knowing how

to use it. Such was the case with Alida Valli who appeared in more than 100

films over the course of a mostly-European career that spanned eight decades.

For all her success playing everything from ingénues to character roles, both

comic and tragic, Italian-born "Valli" (as she was credited during her brief

career away from the continent) made a name for herself in the English-speaking

film world during the late 1940s and early '50s playing some of the movies' most

enigmatic women, fascinating audiences not only with her looks, but with her

ability to simultaneously hide and reveal a character's thoughts and emotions.

Framed beneath a broad forehead and natural auburn hair, her wide, expressive eyes could demonstrate a depth of

emotion while at the same time leaving the audience guessing the true nature of

the thoughts and feelings behind it. From suspected murderesses to wounded young women

clinging to the past, Alida Valli's English-speaking characters were few but

affecting and memorable. And, though frequently less mysterious in nature,

many of her European roles (which demonstrate a much broader array of

characterizations and performances) are equally, if not more, fascinating to watch. Often the difference between ordinary beauties and beauties who find success

in motion pictures is not the degree of photogeneity in the face but knowing how

to use it. Such was the case with Alida Valli who appeared in more than 100

films over the course of a mostly-European career that spanned eight decades.

For all her success playing everything from ingénues to character roles, both

comic and tragic, Italian-born "Valli" (as she was credited during her brief

career away from the continent) made a name for herself in the English-speaking

film world during the late 1940s and early '50s playing some of the movies' most

enigmatic women, fascinating audiences not only with her looks, but with her

ability to simultaneously hide and reveal a character's thoughts and emotions.

Framed beneath a broad forehead and natural auburn hair, her wide, expressive eyes could demonstrate a depth of

emotion while at the same time leaving the audience guessing the true nature of

the thoughts and feelings behind it. From suspected murderesses to wounded young women

clinging to the past, Alida Valli's English-speaking characters were few but

affecting and memorable. And, though frequently less mysterious in nature,

many of her European roles (which demonstrate a much broader array of

characterizations and performances) are equally, if not more, fascinating to watch.

At

one point in Carol Reed's THE THIRD MAN (1949), an intoxicated

Joseph Cotten

elicits a smile from Alida before observing, "That's the first time I've ever

seen you laugh." And indeed, after watching her in so many serious, even

melancholy roles, English-speaking audiences are often surprised to learn that

Alida Valli first made a name for herself in Depression-era Italy in much

lighter fare, including several romantic comedies of

the "telefoni bianchi" (or "white telephone") era of Italian cinema -- so

called because of their opulent, white Art Deco sets, similar to those also seen

in Hollywood in the mid-1930s. (Think

Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers.)

Alida was only fifteen when she first stepped before a movie camera, but her

natural beauty and unaffected charm quickly made her an audience favorite in a

series of popular comedies by director Max Neufeld, including MILLE LIRE AL MESE

("1000 Lira Per Month") and ASSENZA INGIUSTIFICATA ("Unexcused Absence"), both

1939.

|

|

In addition to becoming a popular ingénue in modern stories, "la fidanzate d'Italia"

("the fiancée of Italy"), as she was called, quickly proved herself capable of

adjusting to the atmosphere of period pieces and literary adaptations as well.

In 1940 she played the title role opposite Vittorio de Sica in MANON LESCAUT,

adapted from the 18th century romantic tragedy by French novelist Abbé Prévost,

complete with a blonde wig and pocket hoops. The same year (without the

blonde wig) she played Stendhal's heroine Vanina Vanini opposite one of Italian

cinema's biggest heartthrobs, Amedeo Nazzari, in OLTRE L'AMORE ("More than

Love") (1940), again directed by MANON LESCAUT's Carmine Gallone. But

after more than a dozen film roles in four years, it was her performance as a

strong-willed, independent young wife and mother battling family conflicts,

poverty and personal grief in Mario Soldati's adaptation of Antonio Fogazarro's

19th century romantic melodrama PICCOLO MONDO ANTICO (aka LITTLE OLD-FASHIONED

WORLD) (1941) that earned Alida the prestigious "Premio Nazionale per la

Cinematografia" (or "National Film Prize" -- then Italy's equivalent of Hollywood's

"Oscar") as Best Actress and proved her status as a bona fide dramatic actress,

not just a popular screen personality. She was twenty years old. In addition to becoming a popular ingénue in modern stories, "la fidanzate d'Italia"

("the fiancée of Italy"), as she was called, quickly proved herself capable of

adjusting to the atmosphere of period pieces and literary adaptations as well.

In 1940 she played the title role opposite Vittorio de Sica in MANON LESCAUT,

adapted from the 18th century romantic tragedy by French novelist Abbé Prévost,

complete with a blonde wig and pocket hoops. The same year (without the

blonde wig) she played Stendhal's heroine Vanina Vanini opposite one of Italian

cinema's biggest heartthrobs, Amedeo Nazzari, in OLTRE L'AMORE ("More than

Love") (1940), again directed by MANON LESCAUT's Carmine Gallone. But

after more than a dozen film roles in four years, it was her performance as a

strong-willed, independent young wife and mother battling family conflicts,

poverty and personal grief in Mario Soldati's adaptation of Antonio Fogazarro's

19th century romantic melodrama PICCOLO MONDO ANTICO (aka LITTLE OLD-FASHIONED

WORLD) (1941) that earned Alida the prestigious "Premio Nazionale per la

Cinematografia" (or "National Film Prize" -- then Italy's equivalent of Hollywood's

"Oscar") as Best Actress and proved her status as a bona fide dramatic actress,

not just a popular screen personality. She was twenty years old.

Despite the fact that its fascist government exercised almost total control

over the country's film industry, movie-making in Italy during World War II

was not dominated by propaganda films as it was in other autocratic countries.

Propaganda films were made, but the business of simply entertaining the Italian people

continued in the 1940s much as it had before the war. However, now that

Hollywood movies were effectively banned, Italian movies received renewed attention in

theaters across the country. Alida, now one of the nation's most popular movie

stars, continued to make three or four films a year, some "film calligrafice"

(as prestigious, costume dramas like PICCOLO MONDO ANTICO were called), some

modern romantic comedies like ORE 9: LEZIONE DI CHIMICA (aka SCHOOLGIRL DIARY) (1941) in

which she and her classmates at a girls' boarding school fall in love with their

chemistry teacher, but more and more frequently, modern romantic melodramas and

tearjerkers, including a series of films directed by Mario Mattòli literally

advertised as "i film che parlano al vostro cuore" ("films that touch your

heart"), among them LUCE NELLE TENEBRE ("Lights in the Darkness") (1941) and

CATENE INVISIBILE ("Invisible Chains") (1942), all of which were decidedly

apolitical. |

|

But

the film Alida later cited as the best of her early career, and in which she

gives one of her most memorable performances, was an adaptation of Ayn Rand's

semi-autobiographical novel We the Living that did ruffle some political

feathers.[*1] Released in Italy as two separate films, NOI VIVI ("We the

Living") and "ADDIO, KIRA" ("Goodbye, Kira") in 1942 due to its almost four-hour

running time, the film was directed by Goffredo Alessandrini and stars Alida

as a White Russian university student scraping out a living with her family in Petrograd after

the Russian Revolution, and fighting to maintain her individuality in

the conformist, communist society while torn between her love for a fellow

independent spirit (played by Rossano Brazzi) and her admiration for a communist

police official (Fosco Giachetti) who, though she disagrees with his politics,

seems to be able to live according to his principles with inspirational

dedication. Alida's performance is also inspirational. She conveys

Kira Argounova's emotional turmoil with reserved expressions punctuated by

meaningful momentary glances and subdued gestures appropriate to her outwardly

calm, confident, intelligent character. The performance is at once subtle,

nuanced and powerful. But

the film Alida later cited as the best of her early career, and in which she

gives one of her most memorable performances, was an adaptation of Ayn Rand's

semi-autobiographical novel We the Living that did ruffle some political

feathers.[*1] Released in Italy as two separate films, NOI VIVI ("We the

Living") and "ADDIO, KIRA" ("Goodbye, Kira") in 1942 due to its almost four-hour

running time, the film was directed by Goffredo Alessandrini and stars Alida

as a White Russian university student scraping out a living with her family in Petrograd after

the Russian Revolution, and fighting to maintain her individuality in

the conformist, communist society while torn between her love for a fellow

independent spirit (played by Rossano Brazzi) and her admiration for a communist

police official (Fosco Giachetti) who, though she disagrees with his politics,

seems to be able to live according to his principles with inspirational

dedication. Alida's performance is also inspirational. She conveys

Kira Argounova's emotional turmoil with reserved expressions punctuated by

meaningful momentary glances and subdued gestures appropriate to her outwardly

calm, confident, intelligent character. The performance is at once subtle,

nuanced and powerful.

Though Rand intended her novel as an indictment of

Soviet communism, and Russia was an Italian enemy during World War II, fascist

leaders in Italy eventually came to interpret the film as critical of autocratic

regimes in general, including Italy's fascist dictatorship under Benito

Mussolini, and the film was pulled from theatres after about six months in

release.[*2] Sadly, NOI VIVI did not reappear after the war because it turned

out the film had been made without the consent of Ayn Rand -- it was an

unauthorized adaptation. Though Rand saw the film after the war and

approved of most of it, expressing particular regard for the performances and

production values, there were elements of the adaptation that deviated from the

message she intended the story to convey.[*3] As a result, the film sat in a

vault largely unknown and unappreciated until the 1980s when Rand had the

original two films reedited, removing certain scenes and dubbing others with new

dialogue, before rereleasing it as a single three-hour film with English

subtitles called WE THE LIVING (1986). Though the film's cohesion and

ending were changed, the effectiveness of Alida's performance remains intact.

Memorable Quotations:

- "Non posso lasciarti andare via per sempre." --as Kira Argounova in

NOI VIVI (1942). (translation: "I can't let you go away forever.")

- "Se sappesti come sono infelice. Ho tanta peine con il cuore e

non so perché." --as Giulia in I PAGLIACCI (1943). (translation:

"If you only knew how unhappy I am. I have so much pain in my

heart and I don't know why.")

- "You're my lawyer, not my lover." --as Maddalena Anna Paradine in

THE PARADINE CASE (1947).

|

|

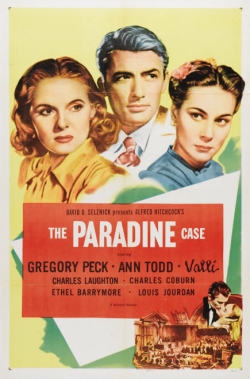

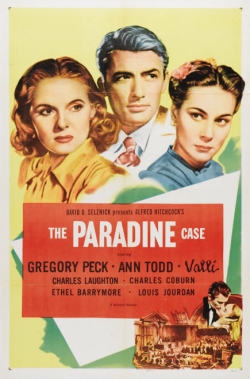

While the Nazis occupied much of Italy after the country's armistice with the

Allies in 1943, Alida managed to evade a summons to go north and appear in

German propaganda films. When the war was finally over, American producer

David O. Selznick offered

her a contract to make movies in Hollywood, and in January 1947 she arrived in

California, was rechristened "Valli" (written in a special ribbon-like script),

and immediately began work on her first English-language film,

Alfred Hitchcock's THE

PARADINE CASE (1947).

Not one of the Master of Suspense's more thrilling movies, the verbose and

overlong courtroom drama stars an odd mixture of veteran stars and

Hollywood newcomers, some of whom seem curiously cast. And yet, in her

Hollywood debut, playing a "strangely attractive" woman on trial for the murder

of her blind, war-hero husband, Valli offers the most engaging and credible

performance in the picture. Did she or didn't she? And her husband's

virile young valet (Louis Jourdan): did they or didn't they? Though far removed

from the expressive, often vivacious characters she had played back home, in sparse

prisoner attire with her hair pulled back, Valli's hauntingly enigmatic screen

presence fulfills its purpose: it keeps the audience guessing while everyone around her -- her defense

attorney Gregory Peck who becomes infatuated with her, his wife Ann Todd who

grows jealous of her, Todd's best friend Joan Tetzel who becomes suspicious of

her, the prosecutor Leo G. Carroll who interrogates her, the judge

Charles

Laughton who disesteems her, and his wife Ethel Barrymore who sympathizes with

her -- talk and talk and talk. While the Nazis occupied much of Italy after the country's armistice with the

Allies in 1943, Alida managed to evade a summons to go north and appear in

German propaganda films. When the war was finally over, American producer

David O. Selznick offered

her a contract to make movies in Hollywood, and in January 1947 she arrived in

California, was rechristened "Valli" (written in a special ribbon-like script),

and immediately began work on her first English-language film,

Alfred Hitchcock's THE

PARADINE CASE (1947).

Not one of the Master of Suspense's more thrilling movies, the verbose and

overlong courtroom drama stars an odd mixture of veteran stars and

Hollywood newcomers, some of whom seem curiously cast. And yet, in her

Hollywood debut, playing a "strangely attractive" woman on trial for the murder

of her blind, war-hero husband, Valli offers the most engaging and credible

performance in the picture. Did she or didn't she? And her husband's

virile young valet (Louis Jourdan): did they or didn't they? Though far removed

from the expressive, often vivacious characters she had played back home, in sparse

prisoner attire with her hair pulled back, Valli's hauntingly enigmatic screen

presence fulfills its purpose: it keeps the audience guessing while everyone around her -- her defense

attorney Gregory Peck who becomes infatuated with her, his wife Ann Todd who

grows jealous of her, Todd's best friend Joan Tetzel who becomes suspicious of

her, the prosecutor Leo G. Carroll who interrogates her, the judge

Charles

Laughton who disesteems her, and his wife Ethel Barrymore who sympathizes with

her -- talk and talk and talk.

Unfortunately, Valli's face alone is not enough to sustain the audience's

interest through two hours of legal and criminal analysis by the rest

of the cast, as well as a few scenes of inner torment and marital discord while

Peck

struggles to prevent his growing obsession with his client from destroying both

his marriage and his career. American critics generally complimented the

film's superficialities while disparaging its languid pace and

Peck's

unconvincing performance as a gray-streaked English barrister. Opinions

were also divided as to whether Valli's effectiveness in her role was due to any

skill on her part, or just her intriguing looks -- some were unconvinced she

could really act. Even back home, Italian critics complained

about the impassivity they viewed in Valli's usually so poetic face. Audiences,

seemingly turned off by the foreign legal setting of the film and the unfamiliar

faces (including Jourdan, Todd and Valli) who populated it, mostly stayed away, and THE PARADINE CASE became the biggest financial failure of

Selznick's storied career.

Multimedia Clips:

-

"The

Paradine Case" (clip) from THE PARADINE CASE (1947) by

Franz

Waxman (a .MP3 file). "The

Paradine Case" (clip) from THE PARADINE CASE (1947) by

Franz

Waxman (a .MP3 file).

(For help opening the multimedia files, visit the

plug-ins

page.) Footnotes:

- interoffice memos from 1948, The David O. Selznick Collection, Harry Ransom Center,

University of Texas at Austin.

- Berliner, Michael S. (editor), Letters of Ayn Rand

(New York: Dutton, 1995): 370.

- ibid. 196.

|

|

Go to the next page.

Page 1 | Page 2 | Page 3

|

|

|

![]() Printer-friendly version.

Printer-friendly version.

![]() Return

to the top.

Return

to the top.

Often the difference between ordinary beauties and beauties who find success

in motion pictures is not the degree of photogeneity in the face but knowing how

to use it. Such was the case with Alida Valli who appeared in more than 100

films over the course of a mostly-European career that spanned eight decades.

For all her success playing everything from ingénues to character roles, both

comic and tragic, Italian-born "Valli" (as she was credited during her brief

career away from the continent) made a name for herself in the English-speaking

film world during the late 1940s and early '50s playing some of the movies' most

enigmatic women, fascinating audiences not only with her looks, but with her

ability to simultaneously hide and reveal a character's thoughts and emotions.

Framed beneath a broad forehead and natural auburn hair, her wide, expressive eyes could demonstrate a depth of

emotion while at the same time leaving the audience guessing the true nature of

the thoughts and feelings behind it. From suspected murderesses to wounded young women

clinging to the past, Alida Valli's English-speaking characters were few but

affecting and memorable. And, though frequently less mysterious in nature,

many of her European roles (which demonstrate a much broader array of

characterizations and performances) are equally, if not more, fascinating to watch.

Often the difference between ordinary beauties and beauties who find success

in motion pictures is not the degree of photogeneity in the face but knowing how

to use it. Such was the case with Alida Valli who appeared in more than 100

films over the course of a mostly-European career that spanned eight decades.

For all her success playing everything from ingénues to character roles, both

comic and tragic, Italian-born "Valli" (as she was credited during her brief

career away from the continent) made a name for herself in the English-speaking

film world during the late 1940s and early '50s playing some of the movies' most

enigmatic women, fascinating audiences not only with her looks, but with her

ability to simultaneously hide and reveal a character's thoughts and emotions.

Framed beneath a broad forehead and natural auburn hair, her wide, expressive eyes could demonstrate a depth of

emotion while at the same time leaving the audience guessing the true nature of

the thoughts and feelings behind it. From suspected murderesses to wounded young women

clinging to the past, Alida Valli's English-speaking characters were few but

affecting and memorable. And, though frequently less mysterious in nature,

many of her European roles (which demonstrate a much broader array of

characterizations and performances) are equally, if not more, fascinating to watch. In addition to becoming a popular ingénue in modern stories, "la fidanzate d'Italia"

("the fiancée of Italy"), as she was called, quickly proved herself capable of

adjusting to the atmosphere of period pieces and literary adaptations as well.

In 1940 she played the title role opposite Vittorio de Sica in MANON LESCAUT,

adapted from the 18th century romantic tragedy by French novelist Abbé Prévost,

complete with a blonde wig and pocket hoops. The same year (without the

blonde wig) she played Stendhal's heroine Vanina Vanini opposite one of Italian

cinema's biggest heartthrobs, Amedeo Nazzari, in OLTRE L'AMORE ("More than

Love") (1940), again directed by MANON LESCAUT's Carmine Gallone. But

after more than a dozen film roles in four years, it was her performance as a

strong-willed, independent young wife and mother battling family conflicts,

poverty and personal grief in Mario Soldati's adaptation of Antonio Fogazarro's

19th century romantic melodrama PICCOLO MONDO ANTICO (aka LITTLE OLD-FASHIONED

WORLD) (1941) that earned Alida the prestigious "Premio Nazionale per la

Cinematografia" (or "National Film Prize" -- then Italy's equivalent of Hollywood's

"Oscar") as Best Actress and proved her status as a bona fide dramatic actress,

not just a popular screen personality. She was twenty years old.

In addition to becoming a popular ingénue in modern stories, "la fidanzate d'Italia"

("the fiancée of Italy"), as she was called, quickly proved herself capable of

adjusting to the atmosphere of period pieces and literary adaptations as well.

In 1940 she played the title role opposite Vittorio de Sica in MANON LESCAUT,

adapted from the 18th century romantic tragedy by French novelist Abbé Prévost,

complete with a blonde wig and pocket hoops. The same year (without the

blonde wig) she played Stendhal's heroine Vanina Vanini opposite one of Italian

cinema's biggest heartthrobs, Amedeo Nazzari, in OLTRE L'AMORE ("More than

Love") (1940), again directed by MANON LESCAUT's Carmine Gallone. But

after more than a dozen film roles in four years, it was her performance as a

strong-willed, independent young wife and mother battling family conflicts,

poverty and personal grief in Mario Soldati's adaptation of Antonio Fogazarro's

19th century romantic melodrama PICCOLO MONDO ANTICO (aka LITTLE OLD-FASHIONED

WORLD) (1941) that earned Alida the prestigious "Premio Nazionale per la

Cinematografia" (or "National Film Prize" -- then Italy's equivalent of Hollywood's

"Oscar") as Best Actress and proved her status as a bona fide dramatic actress,

not just a popular screen personality. She was twenty years old. But

the film Alida later cited as the best of her early career, and in which she

gives one of her most memorable performances, was an adaptation of Ayn Rand's

semi-autobiographical novel We the Living that did ruffle some political

feathers.[

But

the film Alida later cited as the best of her early career, and in which she

gives one of her most memorable performances, was an adaptation of Ayn Rand's

semi-autobiographical novel We the Living that did ruffle some political

feathers.[ While the Nazis occupied much of Italy after the country's armistice with the

Allies in 1943, Alida managed to evade a summons to go north and appear in

German propaganda films. When the war was finally over, American producer

While the Nazis occupied much of Italy after the country's armistice with the

Allies in 1943, Alida managed to evade a summons to go north and appear in

German propaganda films. When the war was finally over, American producer