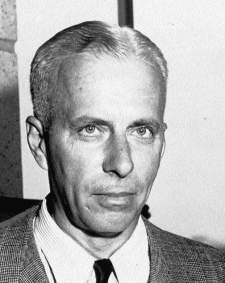

Howard Hawks

Awards | Bibliography | Links | Image Credits | THE BIG SLEEP

An

Ivy League-educated storyteller who worked his way up from assistant prop man to

become a screenwriter, director and producer, all before the movies could even

talk, Howard Hawks eventually became one of the most consistent and commercially

successful independent directors of the Studio System era, excelling in films

ranging from screwball comedies and musicals to westerns, action-adventures and

film noir crime dramas. And though his talents went largely unacknowledged

by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences -- likely due to his discreet

style, which had a tendency to call attention to the personalities and performances of

his stars rather than the the visual framework in which they appeared -- Hawks

did receive an Honorary Oscar for career achievement in 1974. An

Ivy League-educated storyteller who worked his way up from assistant prop man to

become a screenwriter, director and producer, all before the movies could even

talk, Howard Hawks eventually became one of the most consistent and commercially

successful independent directors of the Studio System era, excelling in films

ranging from screwball comedies and musicals to westerns, action-adventures and

film noir crime dramas. And though his talents went largely unacknowledged

by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences -- likely due to his discreet

style, which had a tendency to call attention to the personalities and performances of

his stars rather than the the visual framework in which they appeared -- Hawks

did receive an Honorary Oscar for career achievement in 1974. |

Beginning

with THE ROAD TO GLORY (1925), Hawks directed a handful of silent films for

Fox Film Corp. before the movies began

to talk and his career really took off. For the Prohibition-era crime

drama SCARFACE (1932), Hawks and screenwriter Ben Hecht interviewed colleagues

of Chicago gangster Al Capone and based much of the surprisingly violent plot on

the stories they recounted. Starring Paul Muni as title character Tony

Camonte, SCARFACE depicts a bloody turf war between Camonte's gang and that of

a bootlegger (Boris Karloff), as well as Camonte's struggles to keep control of his

organization and his sister (Ann Dvorak) who has fallen in love with his best

friend (George Raft). Although SCARFACE was part of a wave of gangster

films made during the early 1930s -- foremost among them, LITTLE CAESAR (1930)

and THE PUBLIC ENEMY (1931) -- and was not the most commercially successful of

the genre, owing to its shocking violence, it exhibits an artistry and visual

style which would become less explicit in his films as Hawks' career progressed. Beginning

with THE ROAD TO GLORY (1925), Hawks directed a handful of silent films for

Fox Film Corp. before the movies began

to talk and his career really took off. For the Prohibition-era crime

drama SCARFACE (1932), Hawks and screenwriter Ben Hecht interviewed colleagues

of Chicago gangster Al Capone and based much of the surprisingly violent plot on

the stories they recounted. Starring Paul Muni as title character Tony

Camonte, SCARFACE depicts a bloody turf war between Camonte's gang and that of

a bootlegger (Boris Karloff), as well as Camonte's struggles to keep control of his

organization and his sister (Ann Dvorak) who has fallen in love with his best

friend (George Raft). Although SCARFACE was part of a wave of gangster

films made during the early 1930s -- foremost among them, LITTLE CAESAR (1930)

and THE PUBLIC ENEMY (1931) -- and was not the most commercially successful of

the genre, owing to its shocking violence, it exhibits an artistry and visual

style which would become less explicit in his films as Hawks' career progressed. |

Having

briefly trained as a flier during his service in World War I, Hawks' personal

passion for aviation provided settings and scenarios for several films over the

course of his career, beginning with THE AIR CIRCUS (1928), his first talking

picture (although he didn't direct its talking scenes). Though Hawks' THE

DAWN PATROL (1930), about the internal conflicts of a British squadron in France

in 1915, was later remade by

Warner Bros. in 1938 with Errol Flynn,

shelving his version for several decades, the remake used much of Hawks'

original screenplay, co-written with Seton Miller and Dan

Totheroh, and based on the Oscar-winning story "The Flight Commander" by

John Monk Saunders. Having

briefly trained as a flier during his service in World War I, Hawks' personal

passion for aviation provided settings and scenarios for several films over the

course of his career, beginning with THE AIR CIRCUS (1928), his first talking

picture (although he didn't direct its talking scenes). Though Hawks' THE

DAWN PATROL (1930), about the internal conflicts of a British squadron in France

in 1915, was later remade by

Warner Bros. in 1938 with Errol Flynn,

shelving his version for several decades, the remake used much of Hawks'

original screenplay, co-written with Seton Miller and Dan

Totheroh, and based on the Oscar-winning story "The Flight Commander" by

John Monk Saunders.

But foremost among his aviation pictures is ONLY ANGELS HAVE WINGS which Hawks wrote, produced and directed for Columbia Pictures in 1939. Starring Cary Grant as a tough-as-nails flier in charge of a flock of American pilots running a dangerous South American air mail route, and Jean Arthur as the wayward moll who falls in love with him but can't understand his callous attitude toward life and death, ONLY ANGELS HAVE WINGS is as much about male friendships in the face of constant risk and the pilots' personal and professional jealousies as it is about flying or Grant's off-and-on relationship with Arthur. Featuring strong supporting performances from the likes of Thomas Mitchell and Richard Barthelmess as well as an early screen appearance by Rita Hayworth, ONLY ANGELS HAVE WINGS earned Academy Award nominations for its black-and-white cinematography and special effects. |

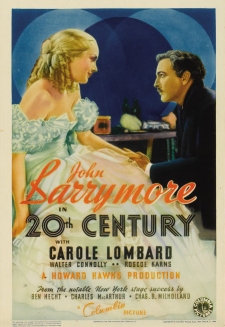

Many

of Hawks' most enduring films are his screwball comedies, a genre many film

historians give him credit for launching with TWENTIETH CENTURY (1934) (named

after the famous New York-Chicago train), which tells the story of a fanatic Broadway producer (John

Barrymore) who turns a shop girl (Carole

Lombard) into a star and lets her go before becoming obsessed with getting

her back. Hawks produced and directed the film, based on the hit play by

Charles MacArthur and Ben Hecht, and imbued the theatrical farce with the quick

pacing that would come to characterize the best of his screwball comedies. Many

of Hawks' most enduring films are his screwball comedies, a genre many film

historians give him credit for launching with TWENTIETH CENTURY (1934) (named

after the famous New York-Chicago train), which tells the story of a fanatic Broadway producer (John

Barrymore) who turns a shop girl (Carole

Lombard) into a star and lets her go before becoming obsessed with getting

her back. Hawks produced and directed the film, based on the hit play by

Charles MacArthur and Ben Hecht, and imbued the theatrical farce with the quick

pacing that would come to characterize the best of his screwball comedies. |

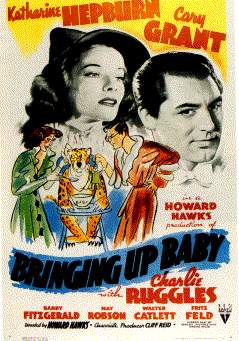

After making a handful of dramas for various studios, Hawks went to RKO to make another comedy, this time based on a short story he'd read in Collier's Magazine about an heiress (to be played by Katharine Hepburn) and a scientist (Cary Grant) chasing a dog in an effort to retrieve a valuable dinosaur bone. Despite its present-day status as a comedic masterpiece (it was ranked #14 on the AFI's list of the 100 Greatest Screen Comedies), at the time of its release, BRINGING UP BABY (1938) was a box office disaster, and Hawks lost his subsequent film assignment at RKO, the action-adventure GUNGA DIN (1939), as a result. Hawks later blamed BABY's commercial failure on the fact that he hadn't included a "normal" character against which to contrast the zaniness and eccentricities of everyone else in the film. However, there was a practical explanation as well. Katharine Hepburn had been labeled "box office poison" by a group of exhibitors shortly before BABY's release, and as a result, RKO did not put the full weight of the studio publicity machine behind the film, believing it a lost cause from the start. |

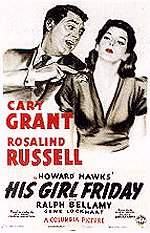

Hawks'

subsequent comedy with Cary Grant, a

remake of Charles MacArthur and Ben Hecht's THE FRONT PAGE (1934), renamed HIS

GIRL FRIDAY (1940), fared much better. For this version of the story of a

big-city newspaper editor who'll stop at nothing to keep his star reporter from

getting married, Hawks came up with the idea of changing the character of the

reporter from a man to a woman, introducing an entirely new dynamic to the

already bewildering relationship between the two. After several of

Hollywood's top screwball comediennes turned down the newly feminized role,

Hawks cast Rosalind Russell as Hildy Johnson,

Grant's star reporter and ex-wife, and

a comedic masterpiece was born. Recognizing the instant chemistry between

his two stars, Hawks allowed Grant and

Russell to ad-lib some of their banter as long as they kept up to Hawks' pace.

Hawks also tacked inconsequential words onto the beginning and end of the

characters' lines so they could overlap their dialog without obscuring the parts

of the lines that the audience needed to understand. The resulting film is

one of the great gems of the screwball comedy genre. Hawks'

subsequent comedy with Cary Grant, a

remake of Charles MacArthur and Ben Hecht's THE FRONT PAGE (1934), renamed HIS

GIRL FRIDAY (1940), fared much better. For this version of the story of a

big-city newspaper editor who'll stop at nothing to keep his star reporter from

getting married, Hawks came up with the idea of changing the character of the

reporter from a man to a woman, introducing an entirely new dynamic to the

already bewildering relationship between the two. After several of

Hollywood's top screwball comediennes turned down the newly feminized role,

Hawks cast Rosalind Russell as Hildy Johnson,

Grant's star reporter and ex-wife, and

a comedic masterpiece was born. Recognizing the instant chemistry between

his two stars, Hawks allowed Grant and

Russell to ad-lib some of their banter as long as they kept up to Hawks' pace.

Hawks also tacked inconsequential words onto the beginning and end of the

characters' lines so they could overlap their dialog without obscuring the parts

of the lines that the audience needed to understand. The resulting film is

one of the great gems of the screwball comedy genre. |

| Current Contest Prize: |

|---|

| Now in Print! |

|---|

| Now on DVD! |

|---|

Buy Videos & DVDs |

|

Buy Movie Posters |

|

Buy Movie Posters |

|

Classic

Movie Merchandise |

|

![]() Printer-friendly version.

Printer-friendly version.

![]() Return

to the top.

Return

to the top.

Last updated:

March 10, 2011.

Reel Classics is a registered trademark of Reel Classics, L.L.C.

© 1997-2011 Reel Classics, L.L.C. All rights reserved. No

copyright is claimed on non-original or licensed material.

Terms of

Use.